- Home

- Anne Stuart

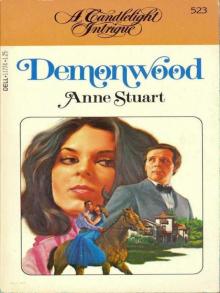

Demonwood

Demonwood Read online

For Bill Maier, with thanks for all his help and for Maria and Lynda ]ean, who like it best.

Published by

Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza

New York, New York 10017

Copyright © 1979 by Anne Stuart

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law.

Dell ® TM 681510, Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

ISBN: 0-440-11774-7

Printed in the United States of America

First printing—September 1979

CLS 10 9 8 7 6 5 43 2 1

PART ONE

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

PART TWO

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

PART ONE

Chapter One

"Are you entirely sure you know what you're doing, Mary Gallager?" my brother Seamus demanded of me. "You know Father never had much good to say for that side of the family."

"Father never had much good to say about anyone," I retorted. "Listen, Seamus, they might offer me a job. That's more than I've come to expect from anyone, friend or relative. And if they offer it to me, I'll take it!"

"But think for a minute, girl," my brother Patrick broke in, his normally placid blue eyes troubled. "Father and Ma have only been dead a month—surely you needn't rush into anything without first giving it careful thought."

I tossed back my heavy mane of hair and snorted ungenteely. "I've had years of giving this careful thought. As long as Father and Ma were alive and needed me I was glad to stay with them. But now that they're gone I need to do something on my own."

"I've not heard many good things about Maeve Gallager Fitzgerald and her fancy husband," Seamus said dourly, shaking his shaggy black head. "You may find yourself hundreds of miles from home, wishing you'd listened to your brothers. After all, it's not as if we didn't have homes for you."

"I don't want to be a poor relation! I want to earn my living just like anybody else." I heard the rising frustration in my voice and forced myself to calm down. I smiled ruefully at Seamus, that great black bear of an Irishman, and said, "Surely you don't think

Peggy would welcome me with open arms into her home. Or Maureen either." I turned to Patrick. "I'm too strong-minded to fit into another woman's household, and if you don't know it they and I do."

"I don't like the idea," Seamus protested. "My little sister forced to earn her living like a common drudge. And from the likes of Connell Fitzgerald! It's just not seemly."

"Seamus, it's the great grand city of Boston in the year of our lord 1897. Times have changed—it's no longer a disgrace for a woman to get a job."

"You should have been born with red hair instead of that black mane," Patrick noted gloomily. "You are the stubbornest female . . ."

I went over the conversation once more in my mind as I sat in the library of Connell Fitzgerald's Beacon Hill mansion. Despite my brave show of defiance to my protective older brothers, I was feeling very frightened and meek indeed, an unusual state of mind for the likes of Mary Gallager. I had always had more than my share of pride and foolhardy bravado. But in the lean weeks that had followed my parents' death I had had to swallow my pride more than once, and it would do me nothing but good. Or so Father McShane always told me. I contemplated the toes of my shiny boots with studied nonchalance, and wondered what the famous Connell Fitzgerald would think of his wife's lowly third cousin as she presented herself for his inspection.

I was not in my best looks that day, more by design than accident. As he walked into the paneled room he would see a woman past the first blush of youth, though perhaps not looking her full twenty-three years. Her sturdy young body would be covered in mourning at least two years out of style, her thick tangle of blue-black curls were hidden beneath the unflattering bonnet she had clamped down upon her head with disgust several long hours ago. Her face was pinched and pale, the generous mouth drawn in a prim fine line, her usually laughing green eyes narrowed and severe. Connell Fitzgerald needed a teacher for his troubled young son, and I intended to get the job. If I had to appear as a stern, destitute female, or had to play upon my tenuous relationship I would do so. The new owners were moving into my parents' house next week, and I intended to be long gone before that happened. For if I had to move in with my brothers I was afraid I would never escape.

"Miss Gallager?" I looked up, startled, at the tall gloomy-looking man in the doorway. "Mr. Fitzgerald will be with you shortly. Could I get you anything? Some tea, perhaps, or sherry?"

Right then I could have done with a stiff belt of the good Irish whiskey my father had kept around for added moral fiber, but I could see that such a request might be looked at askance. So I smiled faintly and shook my head. And waited.

I was both glad and sorry I wasn't to see my cousin Maeve. Perhaps she would have felt the blood tie more strongly, perhaps she'd changed from the spoiled, willful girl I'd known in my youth. Maeve's family had always had more money than my hard-working parents, and their beautiful only daughter, seven years my senior, always made it quite clear to me at the infrequent times we met that the Patrick Gallagers were at best poor relations, at worst as bad an embarrassment to the Matthew Gallagers as any Shanty-boat Irish could be.

No, I doubted I'd have much luck with her. She'd prefer an elegant French nanny to her raw-boned third cousin, and I didn't know if I blamed her. Connell Fitzgerald might prove more amenable—at least, I certainly hoped so. After all, I had always gotten along better with men than with women; perhaps it was caused by being the only daughter with six sons. Women to me had always seemed a little sly and sneaking—you never really knew where you stood with them. No, I would do better with Connell Fitzgerald. I could speak to him frankly, man to man, and not have to worry about secret resentments and hidden motives.

"Miss Gallager?" I jumped nervously, but it was merely the gloomy secretary once more. "Would it be possible for you to come back tomorrow? Mr. Fitzgerald will be tied up for quite some time."

Ah, the curse of Mary Gallager! I was losing my temper, as I was wont to do. With great strength of mind I swallowed the hasty retort that rose to my lips. "I would rather wait, if you don't mind. It's a long trip into town and I'd as soon not have to make it again." Actually, I didn't know if I could afford to come again. I had borrowed the trolley fare from a grudging Seamus, but once it was spent I doubted he would advance me any more toward an object he disapproved of so strongly.

The gloomy man looked even gloomier, his sepulchral voice dropping a notch. "Very well. I can't say how long it will be, though. Mr. Fitzgerald is a very busy man."

My temper flared and broke. "Mr. Fitzgerald asked me to come here today!" I shot back. "I hardly think I'm asking too much of him to keep this appointment." All the half-remembered newspaper clippings and whispered rumors began sneaking back, and I recalled how proud and arrogant the wealthy Mr. Connell Fitzgerald was touted as being. Having experienced his high-handed ways before I'd even met the man, I found I was rapidly beginning to dislike my cousin-by-marriage intensely.

I fell back to contemplating my boots, scowling.

"Certainly, miss," he said emotionlessly.

And in the end I had waited three hours and forty- five minutes when the door finally opened and Connell Fitzgerald strode in.

At that point I could almost have wished he had waited a bit longer. I was at low ebb, tired and nervous and angry. Angry at his careless assumption that I could wait, angry at the intolerable situation I found myself in. Nobly I swallowed my rage as I rose and turned to meet him.

My first reactions to him were a-jumble. I had seen his portrait in the papers so I had a general idea of what he looked like, but I was completely unprepared for the somewhat overwhelming effect of Connell Fitzgerald in the flesh.

He was a tall, strong-looking black Irishman—in general appearance and coloring he was very much like me. His jet black hair curled around a high forehead, his eyes were a deep piercing blue set in a smooth, tanned face. His nose was strong and slightly crooked, his mouth large and thin-lipped, his jaw firm and pugnacious. And on his face was the nastiest expression—combined contempt and boredom with the world in general and me in particular. I told myself that I didn't like him very much. If this was what millions of dollars did to one, then he could keep it.

Those scornful blue eyes swept over my slightly dowdy form, and I stiffened with unconscious pride. "You wanted to see me, Miss Gallager?" he said abruptly, and despite my instant dislike for him I couldn't help but notice the lovely timbre of his voice. It was low-pitched and musical, the kind of voice that could beguile a girl to do almost anything. Some girls, that is.

"There was really no need to see me personally," he continued with cool disdain. "Murphy has full instructions to take care of Maeve's financially embarrassed relatives with discreetness and generosity. I'm sure if you'll simply speak to him on your way out . . ."

This was clearly a dismissal. I stared at the man, dumbfounded, my mouth agape in fury and disbelief, my cheeks flaming. "Mr. Fitzgerald," I said with steely calm, "I came to see you about a position, not for a handout. I don't know which of Maeve's relatives you've been dealing with, but I'll have you know that Patrick Gallager's children wouldn't touch your filthy money if they were starving!" I started for the door with as much dignity as I could muster, which, under the circumstances, was considerable.

"If you're interested in a job then you'd be touching my filthy money anyway," he said reasonably, a trace of amusement in his bleakly handsome face. "What position were you interested in?"

"I heard that your son needs a tutor," I muttered with little grace.

He looked down on my not inconsiderable height with a total lack of concern. "He does. But I'm afraid you wouldn't be suitable. You are my wife's cousin, are you not?" The tone in which he said the word "wife" spoke volumes. "I had in mind someone a little older. And not related. Part of Daniel's problems is his reliance on too many relatives."

I felt panic clutching at my middle. He was dismissing me without even a hearing. Desperately I said, "I'm only a third cousin, sir. I've seen Maeve a handful of times in my life—I don't see that that constitutes a relationship. A mere connection, perhaps."

He raised an eyebrow, seeing me for the first time. "Semantics, Miss Gallager," he dismissed my protest. "And you're still too young." But he signaled me to be seated as he strode behind his highly polished mahogany desk. For some reason I had caught his interest, and I felt the first vague stirrings of unease.

"I'm not too young. I'm twenty-three!" I said defiantly, perching gingerly on the edge of the horsehair sofa. "And I've had experience."

"Twenty-three," he scoffed. "Such a very great age, to be sure." The cold, scornful expression on his face had lightened somewhat, and his eyes held a spark of amusement in them, almost despite himself. "Tell me about your experience, then."

I proceeded to do so. "I was trained at the Simpson Institute for Teachers. I've taught Sunday school and tutored neighborhood children in their studies . . ." This sounded lame even to me.

"And have you done any professional teaching?"

"N . . . n . . . no."

"And have you had any experience with . . . shall we say, troubled children?"

"No," I confessed unwillingly. "But that doesn't mean I wouldn't be good at it. I've always had a way with children-—I know I could do it if you'd only be giving me the chance." I could hear the Irish slipping into my speech as it did when I grew agitated, and I forced myself to calm down. "Mr. Fitzgerald, there's nothing I could do to make you give me the job of tutoring your son. I can only tell you that you'd be making a great mistake if you didn't." I sat back, a little breathless at my daring.

To my amazement his harsh features softened into a smile. A fairly cynical one, to be sure, but a smile nonetheless. And I was aware of the most alarming reaction within me.

"I'd be making a great mistake, would I?" he repeated softly. "Well, Miss Gallager, I've made many mistakes in my life. I suppose I should avoid making any more." There was a note of bitterness in his voice, the same note it had held when he spoke of his wife. He rose abruptly, as if he'd already wasted too much time on me. "Be here tomorrow at nine o'clock with some personal references and my sister will explain the duties."

I had risen when he had and I stared at him with sudden panic. "Are you offering me the job?"

"I thought you practically demanded it," he answered irritably. "Do you want it or do you not?"

Clearly the man was a bully. "I'll let you know tomorrow," I said grandly.

"Miss Gallager," Connell Fitzgerald demanded, "if you don't want the job then why did you come here today?"

I met his dark-blue gaze in the tanned, handsome face candidly. "Oh, I want the job, Mr. Fitzgerald. It's certain things about it that I'm not liking."

"And would you be so good as to tell me what those things are?"

"It's you that I'm not liking," I answered sweetly.

He stared at me in amazement for a moment, then let out a ripple of laughter. "Excellent, Miss Gallager. By all means continue to feel that way. I only hope your dislike of me won't prejudice you against my son. I have the feeling you might be just what he needs."

I rode the trolley home in a grumbly mood. The house in Cambridge seemed colder and emptier than ever as I let myself in the basement door and made my way through the autumn-damp rooms to the big cozy kitchen that was the heart of the house. I kept my mind a perfect blank until I had stirred up the fire in the stove, made myself a cup of strong, peaty tea and settled down with my mother's warm afghan around me. And I sat there, lost in thought, until the sound of someone knocking awoke me from my reverie.

It was Pauline, youngest and dearest of my bevy of sisters-in-law, her pregnant body ponderous, her pretty face alight with curiosity. She'd been my best friend since I was thirteen years old, and her marriage to my brother Luke hadn't diminished the relationship in the slightest.

"Did he offer you the job?" she demanded, helping herself to a cup of the still warm tea and pouring half the contents of the sugar bowl into it.

I settled back into the comfortable rocker. "That he did."

Pauline's sharp brown eyes watched me for a moment. "Then what's troubling you? I thought it was what you wanted above all things—a chance to get away from Cambridge and all your family."

"Not you, Pauline," I protested.

"Yes, even me. It's time you had a life of your own, not living through your sisters and brothers and nieces and nephews. And since you won't have Michael . . ."

"I thought you understood!" I cried, pained by her defection. "There's only going to be one man in my life and I'll know it when I see him." I wrapped the afghan tighter around me. "Michael Flynn is simply not the man."

"Ah ha," said Pauline, and I felt alarm rise in me anew.

"What do you mean by 'ah ha'?"

"Nothing, nothing at all.Just 'ah ha.'" She leaned her plump, pregnant body across the well-scrubbed kitchen table. "And you've met him, then?"

"

Met whom?"

"The man you've been sitting around waiting for for twenty-three years. I must say it's about time—I thought the day would never come."

"I don't know what you're talking about," I denied it hotly. "The only man I met today was Connell Fitzgerald."

"Mary, I've been your closest friend for ten years. Haven't we always been honest with each other?"

"And did it never occur to you that I wasn't caring to be admitting it to myself, much less to you?" I answered roundly.

Pauline leaned forward and put a hand on mine. "Don't fret, lovey. It's not as bad as all that."

"It's not bad at all—the problem is really quite simple. Connell Fitzgerald is a handsome man. I noticed it. A perfectly normal thing, after all. It shouldn't stop me from taking the job." I was arguing more with myself than with her, rocking back and forth nervously.

"A perfectly normal thing, indeed. Except that you've never been really interested in handsome men. What with your six great big strapping brothers you've grown up more like a wild lad than a girl—a bigger tomboy I've never known. More than one young man has complained of your hard heart." She took a deep gulp of her tea and helped herself to the last of my sugar. "If the man's upset you this much then it's more than a natural appreciation of manly beauty. Maybe you shouldn't be taking the job."

"Maybe I shouldn't," I echoed unhappily. "But I've got to get away from here!" I threw aside the afghan and began pacing the brick-floored kitchen. "Pauline, I'll tell you the truth, but you must swear never to tell a soul. I didn't even like him."

"And who says liking has anything to do with loving?"

"For God's sake, I'm not in love! I only just met the man."

"Hush, hush," she soothed me. "Tell me what happened and let me be the judge. You were sitting there in his house, feeling frightened and lonely and unhappy, and in walked . . ."

"Control yourself, Pauline," I said sternly. "He's an attractive man," I admitted against my will. "And a very unhappy, cynical one too. At first I thought he was the coldest, proudest, most disagreeable person I'd ever met."

Ice Blue

Ice Blue Seen and Not Heard

Seen and Not Heard Never Marry a Viscount

Never Marry a Viscount Heartless

Heartless The Devil's Waltz

The Devil's Waltz Hidden Honor

Hidden Honor Silver Falls

Silver Falls Fire and Ice

Fire and Ice Nightfall

Nightfall Never Trust a Pirate

Never Trust a Pirate The Soldier and the Baby

The Soldier and the Baby Still Lake

Still Lake Reckless

Reckless The Spinster and the Rake

The Spinster and the Rake Winter's Edge

Winter's Edge At the Edge of the Sun

At the Edge of the Sun Into the Fire

Into the Fire Night of the Phantom

Night of the Phantom Ritual Sins

Ritual Sins Darkness Before the Dawn

Darkness Before the Dawn Against the Wind

Against the Wind Ruthless

Ruthless The Catspaw Collection

The Catspaw Collection Escape Out of Darkness

Escape Out of Darkness The Widow

The Widow Shameless

Shameless Black Ice

Black Ice Breathless

Breathless Shadows at Sunset

Shadows at Sunset Falling Angel

Falling Angel Housebound

Housebound Cold as Ice

Cold as Ice The Wicked House of Rohan

The Wicked House of Rohan Lord of Danger

Lord of Danger The High Sheriff of Huntingdon

The High Sheriff of Huntingdon Wildfire

Wildfire Moonrise

Moonrise The Demon Count's Daughter

The Demon Count's Daughter Date With a Devil

Date With a Devil To Love a Dark Lord

To Love a Dark Lord Driven by Fire

Driven by Fire Special Gifts

Special Gifts Ice Storm

Ice Storm Shadow Lover

Shadow Lover A Dark & Stormy Night

A Dark & Stormy Night Now You See Him...

Now You See Him... Lady Fortune

Lady Fortune Glass Houses

Glass Houses A Rose at Midnight

A Rose at Midnight Prince of Swords

Prince of Swords One More Valentine

One More Valentine Return to Christmas

Return to Christmas Tangled Lies

Tangled Lies Consumed by Fire

Consumed by Fire The Fall of Maggie Brown

The Fall of Maggie Brown Wild Thing

Wild Thing Crazy Like a Fox

Crazy Like a Fox The Demon Count

The Demon Count Prince of Magic

Prince of Magic Wildfire (The Fire Series Book 3)

Wildfire (The Fire Series Book 3) Anne Stuart's Out-of-Print Gems

Anne Stuart's Out-of-Print Gems Shadow Dance

Shadow Dance Under an Enchantment: A Novella

Under an Enchantment: A Novella Demonwood

Demonwood Blue Sage (Anne Stuart's Greatest Hits Book 3)

Blue Sage (Anne Stuart's Greatest Hits Book 3) Barrett's Hill

Barrett's Hill Angel's Wings (Anne Stuart's Bad Boys Book 5)

Angel's Wings (Anne Stuart's Bad Boys Book 5) Darkness Before Dawn

Darkness Before Dawn The Right Man

The Right Man The Houseparty

The Houseparty Reckless_Mills & Boon Historical

Reckless_Mills & Boon Historical Banish Misfortune

Banish Misfortune Angel's Wings

Angel's Wings Chain of Love

Chain of Love Consumed by Fire (The Fire Series)

Consumed by Fire (The Fire Series) Partners in Crime (Anne Stuart's Bad Boys Book 4)

Partners in Crime (Anne Stuart's Bad Boys Book 4) The Soldier, The Nun and The Baby (Anne Stuart's Greatest Hits Book 2)

The Soldier, The Nun and The Baby (Anne Stuart's Greatest Hits Book 2)